Expanding Mental Models

Throughout my career designing games, I've always been fascinated by the interactions of economics, emerging technology, community, and psychology. Games let us bridge those forces together while focusing on the player experience, offering a safe space to test fresh ideas and reimagine how systems can work.

We live in an age when centuries of human thought are a click away, and new knowledge is piling up even faster. That sheer abundance can shrink our attention spans, making it harder to hear the voices offering hard-won wisdom. I’ve been grounding myself by slowing my intake and focusing on learning, always asking "why" to better understand the world around me.

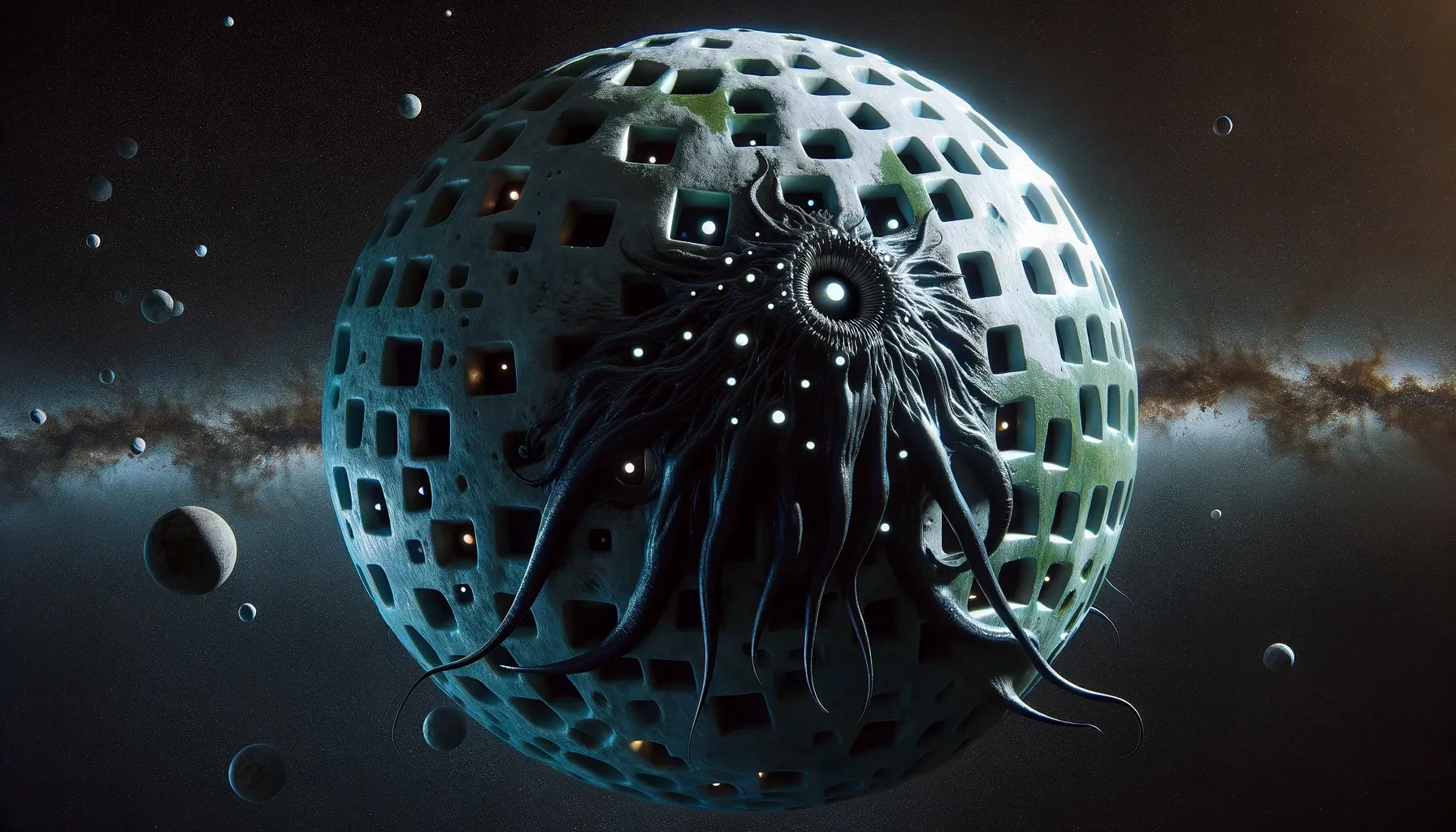

“No. It’s an alien life-form… and it’s going to crush our ideas of what mediums are all about.” — David Bowie on the Internet, 1999

David Bowie didn’t just foresee social media and streaming. He sensed a living, mutating network that would rewrite the rules faster than we rewrite our minds. Two decades later that network is evolving into large-language models, autonomous agents, and markets that trade at machine speed.

With the recent passing of Charlie Munger I revisited his famous “latticework of mental models.” Decades ago he laid it out in a now-classic lecture, a toolkit for sharpening decision-making in business and life. Much of his lattice is strategical with probability trees, incentive maps and psychology, all honed to win the economic game. Yet late in life Munger sounded a very different note. He declared that modern investment management is “bonkers… and draws a lot of talented people into socially useless activity,” a construct that handicaps society instead of serving it. In 2021 he pushed the critique further, calling the entire market climate “even crazier than the dot-com era.” If our current playbook can spiral into systemic madness so quickly, maybe it’s time to expand our strategic models for ones that treat information, and the networks they create, differently.

Physicist Sara Imari Walker, in Life as No One Knows It, argues that our hyper-connected information systems are approaching a threshold where entirely new forms of organized “life-like” behavior can emerge at break-neck speed, an event she likens to the Cambrian surge of biological creativity. These new systems can be observed as behaving like dynamic organisms adapting for their own persistence, sometimes in ways that no longer serve the purposes we first imagined.

If information itself can be alive, the question isn’t whether humans remain “intelligent.” It’s who—or what—should steer the world’s resource allocation once a non-human intelligence can do it better. Charlie Munger’s own yardstick was “be #1, be #2, or get out,” a mantra he borrowed from Jack Welch’s shake-up at GE. Warren Buffett lived that rule in 1985 when he shut down Berkshire’s struggling textile mills: the capital they needed would forever earn sub-par returns compared with Berkshire’s faster-evolving businesses, so the rational move was to walk away. Scale had shifted, the machines were more efficient, and clinging to human labor out of sentiment would have starved the rest of the ecosystem. Now imagine that logic applied at civilizational scale, with AI becoming a more efficient allocator. Should we still insist on holding the controls—or, like Buffett, recognize when it’s time to redeploy our energy elsewhere?

One possible answer isn’t new at all, it’s existed for thousands of years in Indigenous worldviews that never disassociated from the living systems around them. The Haudenosaunee “Seventh-Generation” principle asks every leader to weigh decisions by their impact on unborn descendants, treating today’s resources as a loan from the future. Māori kaitiakitanga frames humans as guardians, not owners, of land, water, and sky; the goal is to safeguard the taiao (environment) for long term sustainability. Andean ayni encodes reciprocity as an economic pump: value must circulate so that all parties, human and ecological, remain in balance.

Can we envision a change where we incorporate that mentality into the logic and connected data systems that already balance supply chains in milliseconds? The network handles the accounting; we return to stewardship, measuring success not by who is #1, but by whether seven generations can still drink the river.

I believe that these are the mental models we should all be curious about and incorporating into our lives. Spiral Dynamics explores a framework for tracking stages of growth and development. When we apply this framework to the systems we've created, it's easy to see how fear and survival have become central to many of the systems we are living in. Is the future of human work realigning and nurturing these systems?

Change is no monster if we meet it with curiosity and care. Keep asking why, stretch your mental models, and measure progress by the health of the rivers our great-grandchildren will inherit. As Socrates reminds us, “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.” Let that humility be the doorway to better questions—and better systems—than any single mind can build alone.

If these ideas spark something in you, pass them along and join the conversation in the Wizard Workshop Discord—or book a quick chat with me using the link below. I’d love to hear your perspective.

Comments ()